AutoZone’s supply chain expansion: A case study

Featuring Josh Bartel and Drew Roth

Guest-at-a-glance

Episode summary

Drew Roth sits down with Josh Bartel to discuss the challenges and opportunities of supply chain expansion. Using AutoZone’s ambitious plan to build 200 new distribution centers as a case study, Josh explores the potential benefits and downsides of multi-echelon networks.

While expanding a company’s geographic footprint can lead to faster delivery and increased sales, Josh cautions listeners about hidden costs. Internal freight costs, outbound shipping expenses, and the complexity of managing inventory across multiple locations can cut into any potential gains.

Josh emphasizes the importance of focusing on local fill rates as a key performance indicator. He advises companies to prioritize optimizing inventory at existing facilities before expanding their network. This episode offers practical advice for any business leader looking to improve their supply chain strategy.

Key insights

Don't confuse network fill rate with success

While expanding your distribution center network might look good on paper — increasing your overall in-stock rate — it can mask inefficiencies. Josh cautions against focusing solely on network-wide fill rates. He stresses the importance of local fill rates, meaning the percentage of orders fulfilled from the DC closest to the customer. A high network fill rate alongside a low local fill rate often indicates an imbalance requiring attention.

Hidden costs can undermine expansion benefits

Before embarking on an ambitious DC expansion project, businesses need to fully grasp the potential hidden costs. Josh highlights internal freight expenses as a common culprit. Moving inventory between DCs to fulfill orders adds up quickly and often goes unnoticed as it’s grouped with general transportation costs. Additionally, increased inventory carrying costs and the added complexity of managing a larger network can significantly impact the bottom line.

Prioritize inventory optimization before expansion

Josh advises companies to exhaust inventory optimization strategies at existing facilities before investing in new distribution centers. Often, companies can achieve significant improvements in delivery speed and customer satisfaction by simply improving inventory management practices at their current locations. This might involve implementing demand forecasting tools, optimizing safety stock levels, and streamlining warehouse operations for greater efficiency.

Test new markets with 3PLs before full expansion

For companies considering expanding their geographic reach, Josh recommends a cautious approach. Instead of immediately investing in new facilities, he suggests partnering with a third-party logistics provider (3PL). This allows companies to test demand and gauge the market’s response to faster delivery times in a new region without the significant upfront costs associated with building or leasing a DC.

Want to learn more? Check out this blog post.

You might also like

AutoZone’s supply chain expansion: A case study

Optimize your offering: Item level net profitability

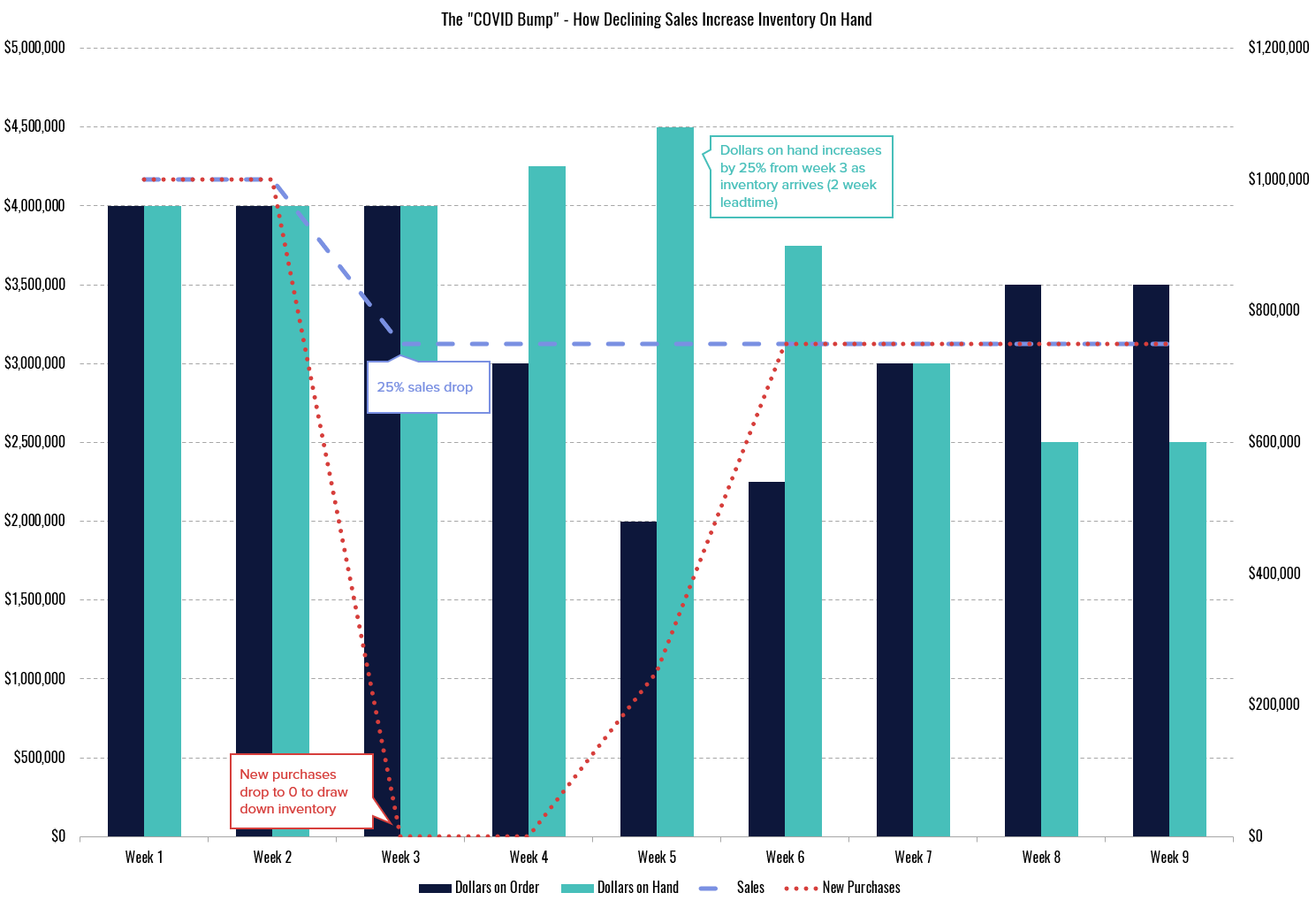

Higher demand and longer leadtimes: The COVID “double whammy”

Subscribe to our newsletter

Get updates on the latest news across all core inventory-related processes.

Subscribe now!

Subscribe

Your email is safe with us, we dont spam.

Want to see how your inventory management stacks up?

We’re so confident in our results, we offer a free performance assessment to all prospective clients. This isn’t a canned sales deck – it’s a bespoke presentation that takes 20 hours of our time. Whether we work together or not, we promise you’ll walk away with useful insights that will improve your business.